The 28th Amendment Project

Giving all Americans the right to be born into a healthy environment that does not cause chronic disease.

The 28th Amendment Project—Giving all Americans the right to be born into a healthy environment that does not cause chronic disease.

|

AMENDING THE U.S. CONSTITUTION Article V of the U.S. Constitution provides two paths for amending the Constitution: Path 1: Path 2: |

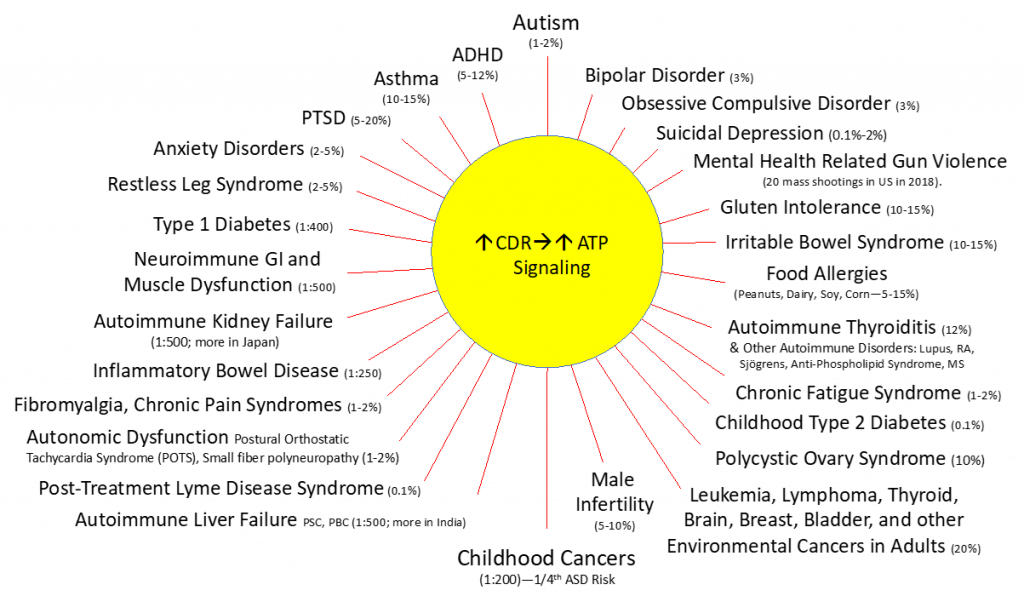

What is more important for the long-term health of a nation than the health of its citizens? A nation grows weak as its people fall to disease. In 1985, 5-10% of children born in the US lived with a chronic disease. Today, just thirty years later, 40% of children live with chronic disease. Many diseases have increased 2-10 times from 1985 to 2015 (Figure 1). Children with chronic disease grow up to be adults with disabilities and disease. This increase in chronic disease is not due to a change in our genes, or a failure in our healthcare system. The increase in disease is the result of measureable chemical changes in our food chain, air, water, and soil. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was given the task of protecting human health by protecting the environment, but economic cuts have handicapped it since its last major contribution to public health, the banning of leaded gasoline in 19961.

|

| Figure 1. 40% of Children Born Today Suffer with Chronic Disease. The prevalence of over 20 diseases has increased 2-to-10-times since 1980s. |

The Naviaux Lab is seeking help to start a movement to create, refine, and ratify a 28th Amendment to the Constitution of the United States. This amendment will enunciate a new right for all American citizens. This is “right to be born into a healthy environment”, an environment that will not cause chronic childhood and adult disease. This right is an inalienable right of citizens of the 21st century. The text of this amendment will serve as a template for similar amendment in all nations of the world.

We didn’t need to think about preserving a healthy environment much in past centuries because the number of humans on the planet was not enough to permanently intoxicate and degrade the natural resources of the biosphere. This situation reached a tipping point in 19882-5. In 1988, there were 5.1 billion people on Earth. In that year, the human population consumed resources and released waste products at a rate the Earth could renew and recycle sustainably. After that, we began to live on biological principle. In 2016, the human population is 7.4 billion. Ever since 1988, we have been consuming natural resources faster than they can be replaced, and releasing waste that is accumulating in both obvious in less obvious places. The Great Pacific Garbage patch is a slow moving swirl of plastics and non-biodegradable detritus that is now twice the size of Texas and continuously releasing pesticides and organic pollutants on a global scale6.

Nanoscale chemical waste is the natural cast-off of an unregulated industrial economy. Many of these chemicals can be shown to produce neurodevelopmental disease during fetal development and in the newborn period. Whole ecosystems have begun to sicken7-9. The Naviaux Lab is developing new mass spectrometry methods that will enable the rapid and regular testing of our environment and food chain to give scientists and policy makers the data needed to crack down on companies and practices that endanger the health of our children, the health of our nation, and the health of the natural world.

Empowering the EPA—Keeping Americans Safe from Pollution

- Establish a permanent Office of Pollution Monitoring (OPM) and an associated observatory network consisting of 50 sentinel cities, with outlying factories, farms, forests, lakes, rivers, and marine coastal sites throughout the United States.

- Create a list of the specific samples to be collected at each of the 50 sentinel sites. These will include GIS-tagged samples of: air, water (from municipal tap and waste, rivers, lakes, well/aquifer/groundwater, and ocean samples), sediments (from specific parks, lakes, reservoir, and marine coastal samples), and regional sentinel foods such as organic and non-organic cow’s milk, honey, corn, soybeans, rice, wheat, oats, fruit (grapes, apples, pears, cherries), strawberries, blueberries, spinach, kale, celery, tomatoes, peanuts, walnuts, almonds, beef, pork, poultry, and fish.

- Collect GIS-tagged samples annually for sites with municipal populations > 1 million, and every 2 years for sites < 1 million, and measure the chemicals, including antibiotics, antifungal drugs, and common pharmaceuticals.

- Create a publicly-accessible electronic database with the results of these surveys as a congressionally-mandated public service.

- Work with the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the American Medical Association (AMA) to correlate the trends of environmental chemical concentrations and the activities that produce them, with the trends of chronic illness in children in the sentinel areas.

- Generate a biannual report that prioritizes for US Congressional action, the chemicals that are found to be associated with the greatest health risks.

Resources

References

- Needleman, H.L. The removal of lead from gasoline: historical and personal reflections. Environmental research 84, 20-35 (2000).

- Wackernagel, M., et al. Calculating national and global ecological footprint time series: resolving conceptual challenges. Land Use Policy 21, 271-278 (2004).

- Landrigan , et al. The Lancet Commission on pollution and health. The Lancet In press, (2017).

- Stoglehner, G. Ecological footprint – a tool for assessing sustainable energy supplies. Journal of Cleaner Production 11, 267-277 (2003).

- Wackernagel, M. & Yount, J.D. The ecological footprint: An indicator of progress toward regional sustainability. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 51, 511-529 (1998).

- Rios, L.M., Jones, P.R., Moore, C. & Narayan, U.V. Quantitation of persistent organic pollutants adsorbed on plastic debris from the Northern Pacific Gyre’s “eastern garbage patch”. Journal of environmental monitoring : JEM 12, 2226-2236 (2010).

- Katagi, T. Bioconcentration, bioaccumulation, and metabolism of pesticides in aquatic organisms. Reviews of environmental contamination and toxicology 204, 1-132 (2010).

- Bonefeld-Jorgensen, E.C. Biomonitoring in Greenland: human biomarkers of exposure and effects – a short review. Rural and remote health 10, 1362 (2010).

- Joyce, S. The dead zones: oxygen-starved coastal waters. Environmental health perspectives 108, A120-125 (2000).