Background

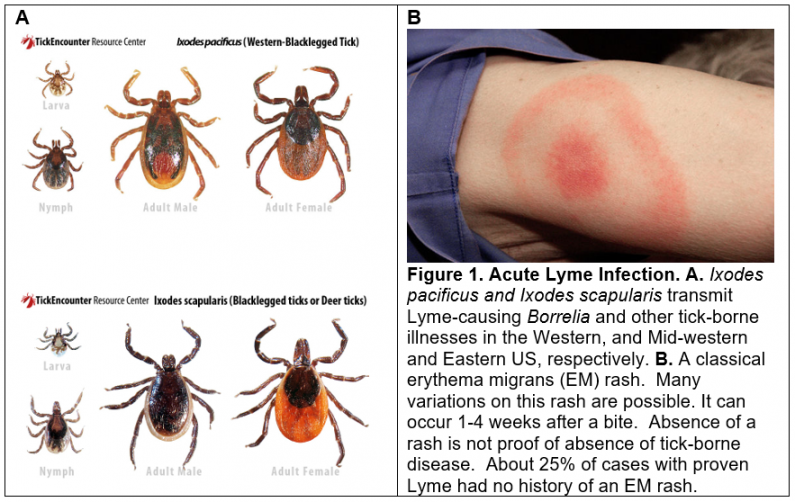

Tick-borne infections cause significant morbidity and mortality around the world1-3. In the US, 400,000 new cases of Lyme borreliosis occur each year4-6. Eighteen tick-borne illnesses that occur in the US are listed in Table 1. These are caused by bacterial, viral, and protozoal pathogens that have co-evolved with ticks and their vertebrate hosts. Recent ecosystem disruptions have been caused by climate change, farming, and industrialization. These disruptions have increased the frequency of human-tick encounters each year over the past 30 years.

In addition to ecosystem and climate changes, chemical changes in our food chain, air, and water have led to primed and dysregulated innate immune responses. We have called this a persistently activated cell danger response (CDR)7. When the CDR fails to return to a normal baseline state, the process of healing is disrupted8, and many different kinds of chronic complex illness can result. Two of these that we have studied are autism spectrum disorder (ASD)9 and myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS)10. About 10% of patients who have acute Lyme disease will go on to develop chronic symptoms of post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome (PTLDS, Box 1).

| Box 1

Diagnostic Criteria for Post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome (PTLDS)11

Positive Western Blot Results—CDC Criteria IgM Positive: two of the following three bands are present: 24 kDa (OspC)*, 39 kDa (BmpA), and 41 kDa (Fla)12 |

New Research

In new research funded by the Steven and Alexandra Cohen Foundation and private donors, we will be using advanced methods in targeted metabolomics and exposomics to answer the following questions:

- Can metabolomics and exposomics be used to diagnose acute Lyme disease?

- Can these methods predict who is at increased risk to develop PTLDS?

- Is there an overlapping chemical signature in PTLDS and ME/CFS?

- Can a new test called “Dynamic Metabolomic Analysis” (DMA) be used to personalize metabolomic results, identify subtypes, and predict outcomes in Lyme or ME/CFS?

Table 1. Tick-Borne Infections

| No. | Pathogen | Tick Vectors | Illnesses |

| 1 | Borrelia burgdorferi | Black legged ticks Ixodes scapularis, I. pacificus, I. ricinius [Europe] | Lyme disease |

| 2 | Borrelia mayonii | Black legged ticks Ixodes scapularis | Lyme disease |

| 3 | Borrelia miyamotoi | Ixodes scapularis, I. pacificus, I. ricinius [Europe], I. persulcatus [China, Japan] | Relapsing fever |

| 4 | Borrelia hermsii, B. parkeri, B. turicatae | Soft-bodied ticks/short biting/long-lived ticks Ornithodoros hermsi (squirrels and chipmunks), O. parkeri (ground squirrels, burrowing owls), O. turicata | Tick-borne relapsing fever (TBRV) |

| 5 | Not yet identified; not B. burgdorferi or B. lonestari | Lone Star tick Amblyomma americanum | STARI (Southern tick-associated rash illness) |

| 6 | Bartonella sp. | I. scapularis, I. pacificus, I. ricinius [Europe] | Cat scratch fever, Bartonellosis |

| 7 | Ehrlichia chaffeensis | Lone Star tick Amblyomma americanum, Wood tick Dermacentor variabilis | Monocytic ehrlichosis |

| 8 | Anaplasma phagocytophilum | Amblyomma americanum, I. scapularis | Anaplasmosis |

| 9 | Rickettsia rickettsia | Wood tick Dermacentor variabilis, D. andersoni | Rocky mountain spotted fever |

| 10 | Rickettsia parkeri | Amblyomma maculatum | Gulf coast rickettsiosis |

| 11 | Rickettsia phillipi (364D) | Pacific coast tick Dermacentor occidentalis | California 364D Rickettsiosis |

| 12 | Francisella tularensis | Wood tick Dermacentor variabilis, D. andersoni; also fleas and mites | Tularemia, Rabbit fever |

| 13 | Babesia microti | I. scapularis, I. pacificus | Babesiosis |

| 14 | Powassan virus (POWV); Flaviviridae | Ixodes cookei, I. scapularis, I. marxi, I. spinipalpusm, Dermacentor andersoni, and D. variabilis | Powassan virus disease |

| 15 | Colorado tick fever virus (CTFV); Reoviridae | Dermacentor andersoni | Colorado tick fever |

| 16 | Heartland virus; Phlebovirus Bunyaviridae | Lone star tick Amblyomma americanum | Heartland tick fever |

| 17 | Tick Borne Encephalitis Virus (TBEV); Flaviviridae | I. scapularis (US), I. ricinus, I. persulcatus [Europe and Asia] | Tick-borne encephalitis |

| 18 | Bourbon virus; Thogotovirus Orthomyxoviridae | Lone star tick Amblyomma americanum, others not yet identified | Bourbon virus disease |

References

- Bellis, J. & Tay, E.T. Tick-borne illnesses: identification and management in the emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Med Pract 15, 1-24 (2018).

- Gutierrez, R.L. & Decker, C.F. Prevention of tick-borne illness. Dis Mon 58, 377-387 (2012).

- Juckett, G. Arthropod-Borne Diseases: The Camper’s Uninvited Guests. Microbiol Spectr 3(2015).

- Moore, A., Nelson, C., Molins, C., Mead, P. & Schriefer, M. Current Guidelines, Common Clinical Pitfalls, and Future Directions for Laboratory Diagnosis of Lyme Disease, United States. Emerg Infect Dis 22(2016).

- Schiffman, E.K., et al. Underreporting of Lyme and Other Tick-Borne Diseases in Residents of a High-Incidence County, Minnesota, 2009. Zoonoses Public Health 65, 230-237 (2018).

- Rebman, A.W., et al. Living in Limbo: Contested Narratives of Patients With Chronic Symptoms Following Lyme Disease. Qual Health Res 27, 534-546 (2017).

- Naviaux, R.K. Metabolic features of the cell danger response. Mitochondrion 16, 7-17 (2014).

- Naviaux, R.K. Metabolic features and regulation of the healing cycle-A new model for chronic disease pathogenesis and treatment. Mitochondrion 46, 278-297 (2019).

- Naviaux, R.K., et al. Low-dose suramin in autism spectrum disorder: a small, phase I/II, randomized clinical trial. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 4, 491-505 (2017).

- Naviaux, R.K., et al. Metabolic features of chronic fatigue syndrome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 113, E5472-5480 (2016).

- Rebman, A.W., et al. The Clinical, Symptom, and Quality-of-Life Characterization of a Well-Defined Group of Patients with Posttreatment Lyme Disease Syndrome. Front Med (Lausanne) 4, 224 (2017).

- Engstrom, S.M., Shoop, E. & Johnson, R.C. Immunoblot interpretation criteria for serodiagnosis of early Lyme disease. J Clin Microbiol 33, 419-427 (1995).

- Dressler, F., Whalen, J.A., Reinhardt, B.N. & Steere, A.C. Western blotting in the serodiagnosis of Lyme disease. The Journal of infectious diseases 167, 392-400 (1993).