Pollution and Human Health

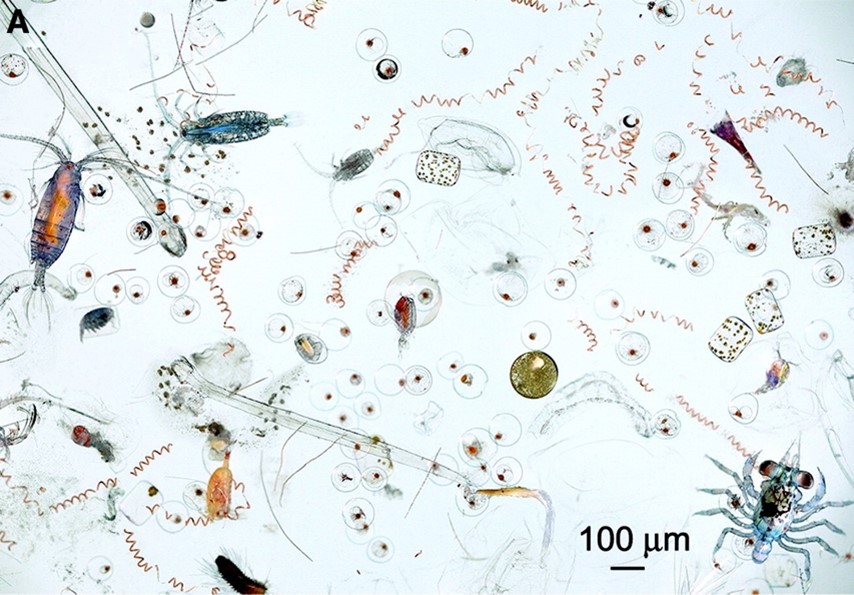

Marine plankton have diversified and adapted to live in all the oceans of the world. How they accumulate and respond to manmade chemicals is giving scientists new insights into the impact of ocean pollution on human health. This image is from a dip net sample from the Pacific Ocean 1.

Background. The Continuous Plankton Recorder (CPR) Survey and mitochondria

- The CPR survey is a program that was started in the UK in 1931 and continues to the present day2.

- Samples of marine plankton are collected between silk sheets using a device towed by ships traveling in key areas around the world.

- These samples are archived and available for scientific study.

-

Mitochondria continuously monitor, integrate, and respond to the presence of environmental pollutants.

-

Chronic and recurrent exposure to environmental pollutants leads to chronic hypersensitivity to ATP-related signaling, and to many chronic childhood conditions and adult illnesses.

The new research

We studied plankton samples from the North Pacific collected from 2000 to 2020 and stored in the CPR archive in the UK3. Manmade pollutants like phthalates, plasticizers, pesticides like chlorpyrifos, perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS, teflons), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH), and antibiotics (including amoxicillin) were found to different degrees in all the samples. The levels and specific chemicals found in plankton varied according to the proximity to human population centers and with temporal trends in usage governed by changing practices in the US, Canada, Russia, China, and Japan over the first 2 decades of the 21st century.

The presence of manmade chemicals in plankton implies that they are also being consumed by creatures like coral, crustaceans, mollusks, and fish, and these in turn, are consumed by marine mammals and birds. In this way, these chemicals are making their way back into the human food chain. Although the concentrations of these pollutants did not rise to levels that are acutely toxic in humans, the effects of the total chemical load on mitochondrial function leads to persistent and recurrent activation of the cell danger response (CDR)4,5. When the local CDR signals are persistently or episodically reactivated, the remote safety signals from the brain that are sent along polyvagal and neuroendocrine circuits are blocked from producing the normal anti-inflammatory and pro-resolving effects needed to complete the healing cycle after any injury or stress.

Chronic inflammation and ATP signaling

Chronic inflammation causes, and is caused by, gradual accumulation of cholesterol and sphingolipids in mitochondria-associated membranes (MAMs) and plasma membranes, and leads to hypersensitivity to eATP-related (purinergic) signaling. Hypersensitivity to eATP signaling blocks recovery and healing from ever-smaller kinds of physical, chemical, nutritional, psychological, socioeconomic, and geopolitical stress, and leads to insecurity, anxiety, and fear, chronic pain, disability, mental health disorders6,7, and other symptoms of chronic illness8,9.

Adult diseases caused by gestational and childhood exposures and early life stresses

When the exposures occur before and during pregnancy and during child development, the worsening exposome from the invisible rising tide of environmental pollutants contributes to the developmental origins of health and disease (DOHAD)10,11. While adult behaviors also contribute to disease, early life stresses (ELS) of many kinds, also called adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), contribute disproportionately to the risk of many chronic conditions and illnesses12. The cost of chronic diseases was $14.1 trillion in 202013. If just a fraction of this money is used to manage and reduce environmental exposures, the rising tide of chronic illness might be slowed or stopped.

Improved environmental health leads to improved human health

The ocean is the last resting place for discarded plastics and pollution, and like freshwater rivers and lakes14, is an early responder to unsustainable human practices and technologies. By monitoring the health of life in the sea as an early warning system, we have a chance to reduce and reverse many of the rising trends in chronic illness that now threaten people around the world15.

Study Documents Available for Download

Media links

- https://today.ucsd.edu/story/marine-plankton-tell-the-long-story-of-ocean-health-and-maybe-human-too

- https://thedublinshield.com/showcase/2023/01/18/plankton-a-new-model-for-human-and-environmental-health/

- https://www.ecomagazine.com/features/plankton-could-hold-key-for-understanding-link-between-ocean-pollution-and-human-health

References

1. Nadeau, J., Lindensmith, C., Deming, J.W., Fernandez, V.I. & Stocker, R. Microbial Morphology and Motility as Biosignatures for Outer Planet Missions. Astrobiology 16, 755-774 (2016).

2. Richardson, A.J., et al. Using continuous plankton recorder data. Prog. Oceanogr. 68, 27-74 (2006).

3. Li, K., et al. Historical biomonitoring of pollution trends in the North Pacific using archived samples from the continuous plankton recorder survey. The Science of the total environment, 161222 (2022).

4. Naviaux, R.K. Perspective: Cell danger response biology-The new science that connects environmental health with mitochondria and the rising tide of chronic illness. Mitochondrion 51, 40-45 (2020).

5. Naviaux, R.K. Metabolic features of the cell danger response. Mitochondrion 16, 7-17 (2014).

6. Pan, L.A., et al. Metabolic features of treatment-refractory major depressive disorder with suicidal ideation. Translational psychiatry 13, 393 (2023).

7. Mocking, R.J.T., et al. Metabolic features of recurrent major depressive disorder in remission, and the risk of future recurrence. Translational psychiatry 11, 37 (2021).

8. Naviaux, R.K. Mitochondrial and metabolic features of salugenesis and the healing cycle. Mitochondrion (2023).

9. Naviaux, R.K. Metabolic features and regulation of the healing cycle-A new model for chronic disease pathogenesis and treatment. Mitochondrion 46, 278-297 (2019).

10. Oken, E., et al. When a birth cohort grows up: challenges and opportunities in longitudinal developmental origins of health and disease (DOHaD) research. J Dev Orig Health Dis 14, 175-181 (2023).

11. Barker, D.J. The origins of the developmental origins theory. Journal of internal medicine 261, 412-417 (2007).

Parise, L.F., Joseph Burnett, C. & Russo, S.J. Early life stress and altered social behaviors: A perspective across species. Neurosci Res (2023).

13. Peterson, C., et al. Economic Burden of Health Conditions Associated With Adverse Childhood Experiences Among US Adults. JAMA Netw Open 6, e2346323 (2023).

14. Malaj, E., et al. Organic chemicals jeopardize the health of freshwater ecosystems on the continental scale. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 111, 9549-9554 (2014).

15. Landrigan, P.J., et al. Human Health and Ocean Pollution. Ann Glob Health 86, 151 (2020).